"It’s about community through my lens, images of loss and hope, and a broad scope of ups and downs. The nostalgia for moments from the past ten years.”

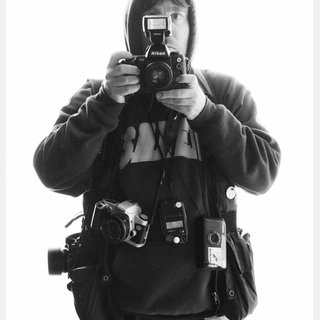

In an inner-west darkroom where negatives soak and images slowly surface, photographer Sam ‘Samoh’ Stephenson continues his conversation with time, process, and memory. His latest exhibition, You Can’t Miss What You Never Had, showing at China Heights Gallery as part of SURPLUS, gathers ten years of film photographs into a reflection on connection, loss, and quiet persistence.

Samoh’s lens has always rested close to the marrow of everyday life. His photographs are intimate and unhurried. They trace friendships, morning rituals, and the remarkable nature of ordinary moments. What began with a high school elective in black and white photography has become a practice intent on resisting the instantaneity that underpins our expectations when it comes photography due to its digitisation. He opts instead for the kind that comes from film soaked in developer, prints dried by hand, and images left to mature across years.

In this conversation, Samoh reflects on film as both discipline and devotion. An anti-pixel practice anchored by the physicality of the print. You Can’t Miss What You Never Had is not a nostalgia trap but a record of noticing, a body of work about the spaces between friends, the light that glances off loss, and the patience required to see something fully.

I’d love to begin by understanding how you came to be the artist you are today. When you think about your influences, what comes to mind?

I took an elective in high school for black and white photography. Developing film is still one of the only things I remember. After school that teacher helped me get into TAFE where I was printing assignments in my neighbours darkroom. From outside of those assignments I was shooting similar to how I do now, skateboarding, portraits, and my surroundings. My colleague at the time gave me a nudge to have my first exhibition after seeing some of my photos on my desk. There was a darkroom attached to the gallery where enlargements were made by a real master. Early education involved watching and re-watching skate videos, reading magazines, online browsing during work hours where photographers' websites were often blocked due to less work getting done while I was working, and more substantial books in city stores.

I’m curious to understand the influence of using film and what you capture. How does this shape the way you connect with your subjects and the world around you?

Shooting film for me is like trying to master something I started. Seeing and visualising what the outcome could be as opposed to seeing a Polaroid or shooting and reviewing continuously on digital. There’s a ‘play it as it lies’ element rather than finessing, too. There are no pixels involved in making this project from shot to print which I’m finding more and more important lately.

How do you recognise when to capture a moment?

There’s usually a connection of some sort or sometimes something presents itself, completely at random. It’s always different depending on the day. The weather plays a part, my mood, time of day, money and emotions. Lots of factors. Walking around you see things. It could be a wind tunnel in the city or a backdrop I find suitable for a future portrait. Or someone making eggs in the morning.

‘You Can’t Miss What You Never Had’ feels full of quiet poetry and longing. What does it mean to you?

The title ties in with ‘Fake Nostalgia’, another project of mine. It’s about my old self and digging through ten years of time and what I have to show for it. To me it’s about shared memories, absent friends, and the life of connections.

How does the feeling behind the title unfold throughout the images in this exhibition?

It’s about community through my lens, images of loss and hope, and a broad scope of ups and downs. The nostalgia for moments from the past ten years. The sequence of one wall of images starts with a dear friend of mine viewing some art. There’s a presence of him through a lot of the photographs.Lots of the ties originally weren’t intentional, but I found new connections once I began to filter through images and make selects.

Your prints add tactility to the images, becoming objects themselves. How do you think about the physicality of the print in relation to the image it holds?

By producing these images from scratch and printing the analogue way it creates something that is a one-off and hard to replicate. It provides the viewer something more substantial than just viewing it on your phone screen.

Developing film invites a lot of patience. What has this taught you about your work, your process, or even about yourself?

I realise that the more patience the better when it comes to the whole process. These days when I take photos I sit with them for periods of time, sometimes years. I let them sit and maybe give them more meaning, or they reveal new life. I think this is especially important these days as there is this need for an endless scroll and instant gratification.

At the end of the day, what do you hope this exhibition invites people to linger?

I read that Rick Rubin book recently and he says something like his work being a reflection of what he’s noticed, not so much facts as thoughts. Some things may resonate, others may not. He goes on to say “Use what’s helpful. Let go of the rest.”. I hope that people take what they want from these photos. Everyone will have their own experience and that’s dope.

Words by Atia Rahim Photos by Alexander Cooke